Role of nutrition in rehabilitation of patients following surgery for oral squamous cell carcinoma

Abstract

Malnutrition in oral cancer patients leads to poor response to treatment and reduced quality of life. The present study assessed the nutritional status of patients treated for oral squamous cell carcinoma and evaluated the need for implementation of any institutional protocol regarding the type of nutritional intervention employed for these patients. Patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma who had undergone primary tumor resection with or without neck dissection and reconstruction from June 2015 to June 2018 were evaluated. Of the patients with complete data recalled for review, only 25 reported to our Institute, including 12 who had undergone surgery alone and 13 who had undergone surgery plus adjuvant radio and/or chemotherapy. Their nutritional status was assessed by measuring their Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) scores, and MNA scores in the groups that underwent surgery alone and surgery plus adjuvant therapy compared by independent sample ‘t’ tests. Mean MNA score was significantly higher in patients who had undergone surgery alone than in patients who had undergone surgery plus adjuvant therapy (p=.001). Postoperative care of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma should include nutritional management to improve patient prognosis and quality of life.

Keywords

Cachexia, Head and neck cancer, Malnutrition, Mini nutritional assessment, Oral cancer, Weight loss

Introduction

Cancer is a major cause of death worldwide and a significant barrier to prolonged life expectancy. The World Health Organization estimated in 2015 that oral cancer was the first or second leading cause of death before age 70 years in 91 countries (Bray et al., 2018). Approximately 657,000 patients per year are newly diagnosed with oral cancer, with over 330,000 patients per year dying of this disease. Treatment modalities for oral cancer include surgery, radiation therapy, targeted drug therapy, and chemotherapy.

Insufficient intake of calories leads to malnutrition among oral cancer patients. Reasons for insufficient oral intake include mechanical obstruction of food, pain, cancer cachexia, and treatment-related oral symptoms (chewing and swallowing problems, pain, dry mouth, sticky saliva, and taste disturbances) (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011). Alcohol consumption, commonly seen amongst cancer patients, also contributes to nutritional problems, as alcohol is regarded as “empty calories,” which reduce appetite and do not provide any essential nutrients (Nugent, Lewis, & Sullivan, 2013).

A malnourished state chiefly manifests as lean muscle depletion, may or may not be accompanied by fat loss, and is responsible for immune depletion. The maintenance of adequate nutritional status prior to, during, and after the course of treatment can minimize postoperative complications and poor responses to treatment. Reduced physical activity, reduced the quality of life, and prolonged hospital stay have been shown to correlate directly with poor nutritional status (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011).

Approximately 75% to 80 % of patients are reported as experiencing severe weight loss issues during cancer treatment (Nugent et al., 2013). A questionnaire study reported that over 40% of patients experienced anorexia and that 64% lost weight during and after treatment (Muscaritoli et al., 2017). Approximately 19% to 45% of oral cancer patients experience severe weight loss prior to treatment, suggesting that malnutrition is common among these patients (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011).

Despite these high levels of malnutrition prior to treatment, few studies to date have evaluated the possible benefits of delaying treatment until patients attain a favorable nutritional status. However, delaying treatment may result in the spread of the tumor in symptomatic patients, especially increasing the risk of a compromised airway. This “delay in administering treatment” approach has been applied to other ailments to increase chances of success but requires further evaluation in cancer patients (Schoeff, Barrett, Gress, & Jameson, 2013).

The present study was designed to evaluate the nutritional status of patients treated for oral cancer using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) scale. This study hypothesized that pain, dysphagia/odynophagia, trismus, radiation-induced mucositis, and other postoperative sequelae result in subacute malnutrition during the period after any treatment for oral cancer. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of malnutrition in patients treated for oral cancer and to evaluate the need for implementation of any institutional protocol regarding the type of nutritional intervention employed for these patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients with primary oral squamous cell carcinoma who underwent surgery with or without adjuvant therapy at the Oral Cancer Institute, Saveetha Dental College, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India, from June 2015 to June 2018 were included in the present study. Patients who underwent surgery for premalignant conditions, recurrent cancer, or any benign condition and patients who underwent surgery for primary or secondary tumors in any region of the body other than the head and neck were excluded. Also excluded were patients with comorbid conditions that would directly impact their nutritional status; patients with missing or incomplete data; and patients who agreed to participate, but failed to report for their appointment.

Of the 114 patients who underwent surgery for oral tumors, 79 underwent primary resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma, with or without neck dissection and reconstruction. The remaining 35 patients underwent surgery for either premalignant conditions or tumor recurrence and were therefore excluded. Of the 79 included patients, four had partially missing data, and 15 had died. The remaining 60 patients were recalled for review; of these, 15 did not respond, whereas 45 agreed to participate in the study. Of these 45 patients, only 25 reported to our Institute for review, including 12 who had undergone surgery alone and 13 who had undergone surgery plus adjuvant radio- and/or chemotherapy.

Patient nutritional status was evaluated using the MNA scale, a simple and effective screening tool that can help identify persons who are malnourished or at the risk of malnutrition. MNA scores have been found to correlate with patient morbidity and mortality. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics committee of the Oral Cancer Institute, Saveetha Dental College (SDC/MDS/18-19/0259), and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation. The normality of the collected data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk numerical test, which found that MNA scores were normally distributed in the groups of patients. Mean MNA scores were compared by independent sample t-tests, with p < .05 defined as statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

The 25 included patients consisted of seven (28%) women and 18 (72%) men participants. Mean age was similar in the 12 patients who underwent surgery alone, and the 13 who underwent surgery plus adjuvant therapy (54.33±15.5 vs 55.77±9.90 years, p=0.783).

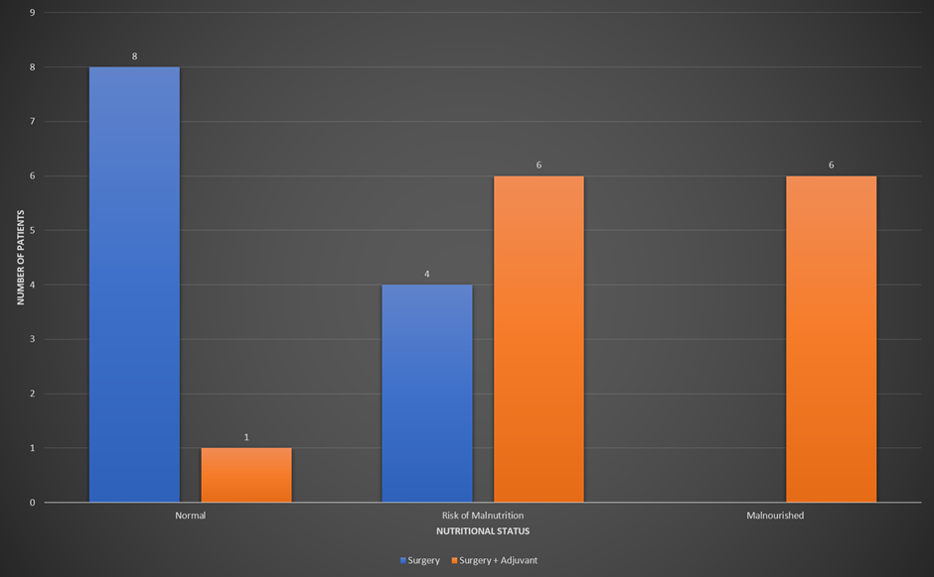

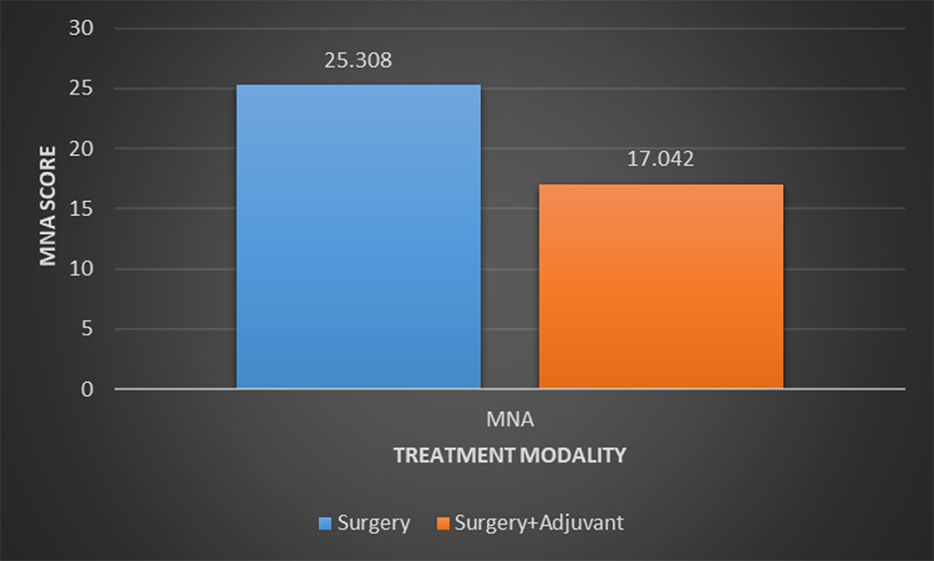

Figure 1 shows the numbers of patients in each group and their nutritional status. Of the 12 patients who underwent surgery alone, eight (67%) had normal nutritional status, and four (33%) were at risk of malnutrition. In contrast, of the 13 patients who underwent surgery plus adjuvant therapy, one (8%) had normal nutritional status, six (46%) were at risk of malnutrition, and six (46%) were malnourished. The mean MNA score was significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery alone than in patients who underwent surgery and adjuvant treatment (25.308±4.39 vs 17.042±4.19, p = 0.001) (Figure 2, Table 1).

|

Group |

N |

Mean ± SD |

Mean Difference |

p-value |

95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Surgery alone |

12 |

25.308 ± 4.39 |

8.266 |

0.001* |

4.708 – 11.824 |

|

Surgery plus adjuvant therapy |

13 |

17.042 ± 4.19 |

*statistically significant by independent sample t-test

Abbreviation: MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment

Malnutrition in patients with oral disease or cancer results from the inadequate intake of macro and micronutrients. One study found that 51% of patients who underwent surgery for cancer had nutritional impairments, including 43% who were at risk of malnutrition and 9% who were overtly malnourished (Muscaritoli et al., 2017).

Moreover, the Malnutrition Advisory Action Group of the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition reported malnutrition in 40% to 80% of patients with malignancies, with malnutrition being an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced illnesses (Nitenberg & Raynard, 2000).

Optimizing adequate nutrition is important during cancer treatment. Adequate nutrition can improve tolerance and response to radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy, improve immune status, increase wound healing, and reduce complications.

Unfortunately, clinicians often overlook the risks of malnutrition in cancer patients, as do many patients and their caregivers. Even when recognized, it is often not addressed appropriately (Nugent et al., 2013).

Malnutrition in cancer patients is a more complex process than simple starvation and can include anorexia, cachexia, and sarcopenia. Inadequate nutritional intake can lead to depletion of body stores of fat and lean mass (Muscaritoli et al., 2017). This ultimately leads to reduced physical function and reduced quality of life.

Clinicians are generally unaware of the need for nutrition management in cancer patients, and oncologists often overlook early steps to prevent malnutrition (Muscaritoli et al., 2017). Dietary status in oral cancer patients is frequently not assessed, despite the negative impact of poor nourishment on prognosis and resistance to treatment.

The present study was performed to raise awareness of the risk of malnutrition in oral cancer patients, and to promote early nutrition screening among at-risk groups. This study was also performed to evaluate the need for early, aggressive treatment to prevention malnutrition as part of routine supportive care in cancer patients.

Malnutrition may manifest as a failure to ingest or retain dietary supplements due to a disease process in the alimentary tract disease process (e.g., an obstructive esophageal tumor), cancer treatment (e.g., radiotherapy causing serious oral mucositis), or cancer-related cachexia or anorexia. Malnutrition is related to poorer survival in patients with any malignancy (Andreyev, Norman, Oates, & Cunningham, 1998; Dewys et al., 1980; Senesse et al., 2008), as well as to poorer responses to surgery (Jagoe, Goodship, & Gibson, 2001; Rey-Ferro, Castaño, Orozco, Serna, & Moreno, 1997) and restorative therapy (Barret et al., 2011; Salas et al., 2008).

Malnutrition can also alter tumor responses to chemotherapy (Andreyev et al., 1998; Dewys et al., 1980; Salas et al., 2008), be associated with extended chemotherapy-related toxicity (Aslani, Smith, Allen, Pavlakis, & Levi, 2000; Barret et al., 2011; Eys, 1982) and reduce patient quality of life (Andreyev et al., 1998; Hammerlid et al., 1998; Monteiro-Grillo, Vidal, Camilo, & Ravasco, 2004; Tian, 2005).

An easy and relevant nutritional assessment tool is needed in everyday oncology practice to identify patients at risk of malnutrition. The MNA is a well-validated nutrition screening and assessment tool for identifying geriatric patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. It is easy to administer, patient-friendly, reproducible, and inexpensive, using two principal criteria: clinical status and comprehensive nutrition assessment (Aggarwal et al., 2013).

This tool includes various factors, such as recent weight loss, loss of appetite, loss of lean body mass, and impairment of physical abilities, and has been shown to have good prognostic and predictive value (Muscaritoli et al., 2017). The MNA can be used in various settings, including in the community, by general practitioners, during home care, and in outpatient settings, as well as in hospitalized and institutionalized patients (Aggarwal et al., 2013).

For example, the MNA was used to assess nutritional status and meal-related situations among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Odencrants & Theander, 2013). Similarly, the present study used the MNA to assess the nutritional status of patients treated for oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Our study found that the mean MNA score was significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery alone than in patients who underwent surgery and adjuvant therapy, indicating that the risk of malnutrition is higher in the latter group. Nutritional status was normal in two-thirds of the patients who underwent surgery alone, whereas almost all patients who underwent surgery plus adjuvant therapy were either malnourished or at the risk of malnutrition. Malnutrition in these patients may be prevented by adequate perioperative nutritional care.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of nutritional status in head and neck cancer patients (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011; Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011).

One study found that, despite sufficient nutritional intake, these patients failed to maintain or improve nutritional status during treatment (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011). Malnutrition was especially significant in patients treated for oral/oropharyngeal cancer, with swallowing problems significantly related to malnutrition (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011).

Malnutrition in patients prior to surgery is a risk factor for postoperative mortality and morbidity. Although attention has been paid to the importance of postoperative nutritional support, patient outcomes may be improved by preoperative nutritional support. Patients should be informed about proper nutritional requirements immediately after diagnosis and to continue these measures perioperatively until there are no signs of malnutrition.

The current dietary recommendations to preserve lean mass in ambulatory patients include intake of 30 to 35 kcal/kg body weight and 1.2 to 2.0 gm protein/kg body weight. However, the optimal intake of energy and protein to preserve lean mass in patients with head and neck cancer is still unknown (Jager-Wittenaar et al., 2011).

High consumption of fruits and vegetables was reported to have a protective effect against the development of oral cancer due to their high content of vitamin C, carotene and other carotenoids, which act as efficient antioxidants, preventing damage to chromosomes, enzymes, and cell membranes caused by the peroxidation of free radicals (Jadhav & Gupta, 2013). It is also important to monitor progression in the dietary state because a loss of body fat may alter physical well being related to patient quality of life.

A primary limitation of this study was its focus on post-operative nutritional assessment, without considering preoperative status, which has been proven to play a role in postoperative recovery. Further, studies with greater numbers of patients may help generate protocols for the nutritional management of oral cancer patients, as adequate nutrition is essential for the rehabilitation of patients treated for oral squamous cell carcinoma.

An experienced interdisciplinary team is required to care for oral cancer patients. Many factors can impede the instant improvement in nutrition, such as the time required for primary cancer therapy. In addition to nutrition, other aspects of patient care, including emotional support and physical activity, correlate with patient quality of life, survival, and other metrics.

Conclusion

Risk of malnutrition was higher in patients who underwent surgery plus adjuvant therapy than in patients who underwent surgery alone. Oral cancer patients require routine nutritional screening and assessment for malnutrition. The care of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma should include peri-operative nutrition management. The inclusion of nutritional care with the primary treatment option requires a patient-centric approach. A multidisciplinary team that is experienced and efficiently coordinated is better positioned to provide high-quality care, especially to patients undergoing multimodal treatment. Early identification of nutritional risk with appropriate consideration of diet can reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality rates.